High and Low (1963)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”High and Low Kurosawa” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Sadly Akira Kurosawa is mostly known for his Samurai films, and some of his greatest works were outside of the Samurai genre (like John Ford’s films outside of his Westerns.) High and Low is one of them, as it tells a story about a wealthy industrialist whose family is the target of a cold-blooded kidnapper. High and Low is not only one of Akira Kurosawa’s best films but its also one of the greatest thrillers ever made. The film was originally an American thriller, based on Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom in 1959 and this is the first and only time Kurosawa ever used material that was from an American origin. What Akira Kurosawa did with the original material was shape it to produce a film that was a reflection and a contemporary map of Japan that ranges from the complacent and the rich, to the needy world of drugs, despair, and the poor. It’s slightly ironic that Kurosawa decided to do a remake when most of his films are remade by others, most famously The Seven Samurai which was remade into The Magnificent Seven, Rashomon which was a remade into The Outlaw, Yojimbo which was remade into A Fistful of Dollars and just about everything from The Hidden Fortress from the storyline to the characters, was remade into George Lucas’s sci-fi blockbuster Star Wars. [fsbProduct product_id=’775′ size=’200′ align=’right’]What is fascinating is the unique layout of the film, because there’s no real center of the story, and more two different halves. The first half explores the character of Gonzo and his struggling moral dilemma of willing to lose everything, all for a child that is not even his. The second half of the film is straight forward police procedural which focuses on Tokura and his men following clues, conducting interviews and investigating old audio tapes and photographs, to try and catch the kidnapper. In some ways Gonzo and the kidnapper are both very similar characters, because they both are power-hungry individuals who will crush whoever tries to get in their way of their diabolical get rich schemes, the only difference between the two of them is one works within the law and one works outside the law. High and Low is a masterfully well crafted thriller, but its also a social commentary on the rich and the poor, a criticism on corporate life and on Japanese society in the early 60’s, showing that sometimes the poor can exploit the rich. In one of the most disturbing sequences in all of Japanese cinema, Kurosawa takes audiences into the grim city of Yokohama, where we are taken in the murky world of bars, drug-ridden alleyways and cheap hotels. When upon entering a location nicknamed ‘Dope Alley’, you witness a disturbing crypt-like alley full of heroin and drug abusers just laying on the pavement like corpses and lepers, as it is a gritty side of Japan that you’ve never seen.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”High and Low Kurosawa” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Sadly Akira Kurosawa is mostly known for his Samurai films, and some of his greatest works were outside of the Samurai genre (like John Ford’s films outside of his Westerns.) High and Low is one of them, as it tells a story about a wealthy industrialist whose family is the target of a cold-blooded kidnapper. High and Low is not only one of Akira Kurosawa’s best films but its also one of the greatest thrillers ever made. The film was originally an American thriller, based on Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom in 1959 and this is the first and only time Kurosawa ever used material that was from an American origin. What Akira Kurosawa did with the original material was shape it to produce a film that was a reflection and a contemporary map of Japan that ranges from the complacent and the rich, to the needy world of drugs, despair, and the poor. It’s slightly ironic that Kurosawa decided to do a remake when most of his films are remade by others, most famously The Seven Samurai which was remade into The Magnificent Seven, Rashomon which was a remade into The Outlaw, Yojimbo which was remade into A Fistful of Dollars and just about everything from The Hidden Fortress from the storyline to the characters, was remade into George Lucas’s sci-fi blockbuster Star Wars. [fsbProduct product_id=’775′ size=’200′ align=’right’]What is fascinating is the unique layout of the film, because there’s no real center of the story, and more two different halves. The first half explores the character of Gonzo and his struggling moral dilemma of willing to lose everything, all for a child that is not even his. The second half of the film is straight forward police procedural which focuses on Tokura and his men following clues, conducting interviews and investigating old audio tapes and photographs, to try and catch the kidnapper. In some ways Gonzo and the kidnapper are both very similar characters, because they both are power-hungry individuals who will crush whoever tries to get in their way of their diabolical get rich schemes, the only difference between the two of them is one works within the law and one works outside the law. High and Low is a masterfully well crafted thriller, but its also a social commentary on the rich and the poor, a criticism on corporate life and on Japanese society in the early 60’s, showing that sometimes the poor can exploit the rich. In one of the most disturbing sequences in all of Japanese cinema, Kurosawa takes audiences into the grim city of Yokohama, where we are taken in the murky world of bars, drug-ridden alleyways and cheap hotels. When upon entering a location nicknamed ‘Dope Alley’, you witness a disturbing crypt-like alley full of heroin and drug abusers just laying on the pavement like corpses and lepers, as it is a gritty side of Japan that you’ve never seen.

PLOT/NOTES

The opening of the film shows a wealthy executive named Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) living a very comfortable life with his wife and loving son, on a large mansion estate located high on the mountains for everyone in Yokohama to see. Gondo is a man trying to gain as much control over the company he works for called National Shoes; and at this point only runs the factory. The directors of National Shoes come to see him at his home and tell him they want the company to start making shoes more cheaply with low quality to impulse the market because Gondo’s sales have recently been flat. Gondo doesn’t agree with them and wants to stick with sturdy, well made but unfashionable shoes.

Gondo believes that the long-term future of the company will be best served by well made shoes with modern styling, but this plan is unpopular because it means lower profits in the short-terms. His employees say that most customers flock to stylish designs and affordable prices and believe their shoes are more practical. They believe the real problem is the President and they want to join forces to vote him out asking Gondo to join them. They tell Gondo he is a potential candidate to be the new President but it will most likely go to another employee with Gondo becoming executive director. Gondo declines believing the President may be old-fashioned but he at least sells quality shoes and not trash and orders Kawanishi who is his right hand man to escort the directors out of his house. Gonzo’s wife sees them leaving and asks her husband what the problem was; with Gonzo of course leaving his wife in the dark about his business affairs.

His son Jun and his playmate Shinichi run throughout the house dressed in cowboy gear shooting toy guns at each other. They then decide to change outfits and Gonzo asks Jun if it’s his turn to be the outlaw. Gonzo then tells his son, “Well, don’t run. Hide and then ambush the sheriff. A man must kill or be killed. Now go, and don’t lose.” His wife is angry at Gonzo’s comments and says, “success isn’t worth losing your humanity.” Gonzo just blows her off and says a woman can’t understand. Suddenly the phone rings and Kawanishi answers it and the caller is for Gonzo.

After the phone call Gonzo finally reveals to his wife and his assistant Kawanishi what he has secretly plotted for years. He tells them how his share in the company isn’t 13% and that he bought 15% more over the past three years and that phone call was just another 19% with is in total of 46%; which is more than what the President of National Shoes has. He then explains how he secretly set up a leveraged buyout to eventually gain total control of the company mortgaging everything he has; including his home. Right now he only has one-third of the amount and will get the rest when he gains control of the company. Gonzo then says, “it was a risky move but National Shoes is mine.”

The phone rings once again and Gonzo answers it. “What? You’ve kidnapped my son?” Gonzo asks the caller. The caller tells Gonzo he has kidnapped his son Jun and wants a total of thirty million yen. Gondo is prepared to pay the ransom saying, “I’ll get him back, no matter what it costs.” But the call is dismissed as a prank when Jun suddenly walks in from playing outside. “What kind of sick joke is this?” Gondo asks. However, Jun’s playmate, Shinichi, the child of Gondo’s chauffeur Aoki, is missing and they realized that the phone call was real and the kidnappers have mistakenly abducted him instead. Gondo tells Kawanishi to call the police saying that the kidnappers will have to return Shinichi knowing a chauffeur can’t possibly pay the ransom; even though he was told by the kidnapper not to inform the police.

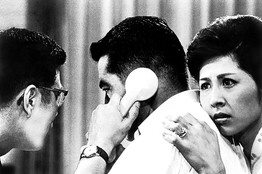

The police soon arrive disguised as department store deliverers and tell Gondo to close all the blinds in the room just in case the man is looking through a telescope. The man in charge of the police investigation is Chief Inspector Tokura and his men install a listening device on the phone so he can listen in on the kidnappers calls. Gonzo arrogantly thinks that the kidnapper will return the chauffeur’s son; because he can’t pay the ransom but Tokura says that he might still harm the child. Tokura says, “kidnapping cases are difficult. The hostage is his protection. We must be especially careful in this case.” He then says that the kidnapper asking for thirty million is a extraordinary amount and that he might be mentally disturbed. The kidnapper calls again with the police listening in and they afterwards listen to the recording. The kidnapper says, “I got the wrong boy. But before you start celebrating listen: I don’t care whose boy it is. You’re still paying. Pay the 30 million or the boy dies. Taking the wrong boy was a lucky break. You’re a fool to pay, but pay you must. You won’t let him die. You don’t have the guts Gondo.”

Gondo laughs at the situation trying to not let this kidnapper ruin his pride and humiliate him. He starts yelling, “make me throw away my hard-earned money! He wants to make a laughingstock out of me. I’ll say this loud and clear: I won’t let him. I won’t pay.” Everyone in the room is quite and Gondo’s wife speaks up saying that Shinichi was kidnapped by mistake and that Gondo would have paid for their own son. Kawanishi steps in and tells her that if Gondo gives him the full amount it will financially ruin him because he mortgaged everything on the company. But Tokura says if Gondo doesn’t pay there is a great chance the kidnapper might kill Shinichi.

Kawanishi was supposed to take a plane to Osaka to deposit a check for Gondo but Gondo postpones it when the kidnapper calls once again. The kidnapper this time lets Shinichi talk to let Gondo know he’s alive and hangs up. Aoki the father of Shinichi starts begging for Gondo to pay the ransom getting on his knees pleading, “until I heard his voice I couldn’t bring myself to do it. But now I’m begging you. I’ll do everything you want until the day I die.” Gondo tells him to stop begging and to get off his knees.

The next morning Gondo tells Tokura and the other officers he can’t pay because he will go under and lose everything. His wife interrupts and says that Gondo must pay. Gondo then tells her, “Listen: you know what’ll happen if I pay? I’ll be penniless…no, worse. I’ll be saddled with debt and forced out of the firm. You don’t know the first thing about poverty. From the day you were born you’ve had big houses and cars, servants tending to your every whim. Your whole life has been a luxury. Maybe I could start over…but you…never!” He tells her how he can’t sacrifice everything for Shinichi and that he’s got to think of Jun, her and his own survival and still refuses to pay. When Gondo tells Kawanishi to take the check and fly to Osaka like he earlier planned Kawanishi is now having second thoughts. He tells Gondo that if he flies there and closes the deal for Gondo to own National Shoes Gondo will later be hated by the public for sacrificing a child and no one would buy his shoes.

Gondo can see that there is a reason for Kawanishi’s sudden change of heart since he was happy to deliver the check the other day. He then figures out that Kawanishi made a deal with the three directors of National shoes and sold Gondo out. Gondo orders Kawanishi to get out of his home but before Kawanishi leaves he tells Gondo he will soon be hearing those words from National Shoes as well. After Kawanishi leaves Tokura tells Gondo that when the kidnapper calls to tell him he will pay even though he wont; just to give the police more time. When the kidnapper calls again Gondo tells him he will pay and they come to terms of letting Gondo see the boy before paying. The kidnapper then orders Gondo to get two briefcases and put the 30 yen in them and to take them on tomorrow’s Kodama No. 2 express train. After getting off the phone Gondo has a change of heart and decides to call the Tokyo bank to ask for a withdrawl of 30 million yen; realizing paying the ransom is the right thing to do.

The next day Gonzo aboard’s the train with detective Tokura and a few of his men holding the two briefcases of cash. While on the train one of Tokura’s men says to Tokura, “I waste no love on the rich, since I grew up poor. At first I despised him, now…” The kidnapper calls the train to speak to Gondo and informs him that Shinichi will be at the foot of the bridge near the Sakawa River. He is then told to throw the briefcases out the washroom windows when the train passes the other side of the bridge. Since there is no stop until Atami the kidnapper will have a large amount of time to get away after receiving the brief cases.

When thrown from the window you can see from the distance a figure running towards the thrown briefcases and like the kidnapper promised Shinichi is later found and unharmed as Tokura says to his men, “We can’t rest until we find that kidnapper. For Mr. Gondo’s sake, be bloodhounds!” The second half of the film is about detective Tokura and his men now looking back into the case searching for clues to catch this criminal and bring him to justice. Kurosawa now brings in the police procedural genre of the postwar period and whats interesting about the second part of the film is that Kurosawa shows us the kidnapper right from the beginning, after receiving the ransom money.

Kurosawa shows us where the boy lives, which is in a studio apartment in a poorer crummier area right outside of Yokohama. It shows how the boy can view Gondo’s large mansion by just looking up and seeing the house larger than life on the hills, when he’s leaving to go to work everyday. The kidnapper at his home reads the ransom story in the paper on how Gondo threw his whole fortune away and how police are mobilized on the case. He’s also hearing stories on the radio on how Gondo is getting much sympathy and is looked at as a hero from the public for the sacrifice he made.

At Gondo’s home Tokura and his men show the 8mm videos and pictures that they took at the moment the money was dropped to Gondo and his family. Tokura knows at that moment two people were involved in the kidnapping including a woman who was holding Shinichi but they can’t make a identification. He got the model of the vehicle the kidnapper used from skid marks and leaving behind paint scrapings. When they question Shinichi his father Aoki tells his son to concentrate more on what he remembers and what he says to the police. Shinichi can’t remember seeing much since the kidnappers covered his face with gauze. At the police station Tokura’s men go over all the clues on Gondo’s location and the phone booths in the perimeter of Gondo’s house. Listening back at the phone recordings the police can also narrow down the vicinity of the kidnappers location on where they held Shinichi.

Meanwhile they question many witnesses who believe they saw the kidnapper with the child and even question the associates at National Shoes suggesting they may be behind the kidnapping because of a grudge with what Gondo had done to them. They eventually get a call that they found the car they were looking for abandoned, while one of Tokura’s men narrows down which trolley the kidnapper used by listening to one of the phone recordings. The next day the police want to take Shinichi for a drive around the shore to see if anything will jog the child’s memory; but already realize that Aoki has taken his son out to do it as well. When catching up with Aoki and Shinichi, Shinichi leads the police to the hideout where Shinichi was kept prisoner. The bodies of the kidnapper’s two accomplices are found there who were passed drug abusers. They were killed by a lethal overdose of pure heroine which was purposely done by the kidnapper because his accomplices tried to blackmail him.

When the kidnapper reads in the paper that the briefcases that were used in the ransom were specifically made to stand out, the kidnapper empties the money out and decides to burn the briefcases. Of course the kidnapper doesn’t know the police rigged the briefcase so when tampered would release a pink like substance. When going to the junkyard and dumping the two briefcases in the city’s public incinerator; the smoke from the incinerator comes out pink and fills the night sky. The investigators question the employees at the junkyard and they describe the man who dumped the brief cases as a young intern from a hospital; which would make him knowledgeable on drugs and drug abuse.

The investigators go to the hospital and see the young intern whose name is Takeuchi and they notice a bandage on his right hand that was described and drawn by Shinichi. Tokura and his men lay a trap for Takeuchi by first planting a story in the newspapers implying that the accomplices that were found dead from a heroin overdose are actually still alive, and then they forge a note from them to the kidnapper demanding more drugs, or they will talk. When Takeuchi reads the forged note; he believes it and that evening drives down to the murky world of bars, drug-ridden alleyways and cheap hotels in the city of Yokohama, to buy more lethal uncut heroin for his accomplices; while the police follow him not too far behind.

Kurosawa shows a grim luridness in this scene where there’s a location nicknamed ‘Dope Alley’ full of heroin and drug abusers just laying on the pavement like corpses and lepers while Takeuchi goes through to purchase and also test the heroin on an active user. The lethal heroin does work as the police later find the woman he used some of the heroin on dead in the alleyway. This sequence in the film is a really creepy and disturbing scene that shows a gritty side of Japan that I’ve never seen in film before.

At the end of the film Takeuchi returns to the home of his dead accomplices to deliver the lethal uncut heroin and is finally apprehended by Tokura and his men. When Tokura comes out and arrests him he shouts, “Takeuchi, you’re gonna hang!” Takeuchi tries to quickly swallow the uncut heroin but is stopped in time and arrested. Most of Gondo’s money is recovered, but it’s unfortunately too late to save Gondo’s property from auction and he looses everything. Now with Takeuchi facing a death sentence, he and Gondo finally meet face to face in prison before his execution.

Takeuchi smiles when finally confronting Gondo and thanks him for coming to see him. Takeuchi asks how he is doing and Gondo says, “making shoes again. It’s a small company, but the owner gives me free rein. I’m working hard to rival National Shoes.”

When Takeuchi reveals to Gondo why he did what he did, his explanation is so simple and understandable that anyone who lived poor could understand his motives. “My room was so cold in winter and so hot in summer. I couldn’t sleep. From my tiny room, your house looked like heaven. Day by day I came to hate you more. It gave me a reason for living. Besides, it’s amusing to make fortunate men taste the same misery as the unfortunate. You want my life story? Forget it. I won’t share my tales of woe to earn your sympathy. I’m glad my mom died last year so I won’t be sickened by her pathetic slobbering. I’m not afraid of death. I don’t care if I go to hell. My life has been hell since the day I was born! ”

ANALYZE

Akira Kurosawa’s propensity for adapting European classics—Dostoyevsky (The Idiot), Shakespeare (Throne of Blood), Gorky (The Lower Depths)—earned him a label, both abroad and at home, as the most “Western” of Japanese directors, even though he never saw himself as other than purely Japanese. Indeed, what could be more Japanese for a man of Kurosawa’s epoch and social class than to have been brought up on Shakespeare, Balzac, and Dostoyevsky, on Beethoven and Schubert? He was born in 1910, when the Meiji era’s enthusiasm for foreign culture had not yet been overwhelmed by rising nationalist tides, the son of an ex–army officer and school administrator of distinguished samurai descent. It would be more accurate to say that for the young Kurosawa such European models had already been so thoroughly assimilated as to form part of his native culture; and far from being exotic transplantations, Throne of Blood and The Lower Depths are richly detailed explorations of the periods and milieus of Japanese history in which Kurosawa sets them.

High and Low represents quite a different project: a contemporary rather than a period film, the adaptation not of a European classic but of an American thriller, Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom (1959), in the era before such thrillers enjoyed much cultural prestige. It is the only time Kurosawa ever worked explicitly with material of American origin (although Yojimbo bore a large debt to Dashiell Hammett, then only slightly more prestigious), and he used it not to illuminate a vanished epoch but to produce a map of contemporary Japan that ranges from the complacent and affluent “heaven” to the needy and nihilistic “hell” of the film’s Japanese title, with an efficient police force patrolling the problematic zone where high and low collide. Kurosawa had treated modern themes before, to be sure. But High and Low is more detached in its effect: less heartrending than Ikiru, less savage (though no less contemptuous) in its criticism of corporate life than The Bad Sleep Well, less romantic in its attitude toward criminality than Drunken Angel. The tormented young policeman played by Toshiro Mifune in Stray Dog has grown up, perhaps, to be the coolly restrained detective embodied by Tatsuya Nakadai: seeing everything but keeping his judgments to himself until he really can’t take it anymore.

High and Low represents quite a different project: a contemporary rather than a period film, the adaptation not of a European classic but of an American thriller, Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom (1959), in the era before such thrillers enjoyed much cultural prestige. It is the only time Kurosawa ever worked explicitly with material of American origin (although Yojimbo bore a large debt to Dashiell Hammett, then only slightly more prestigious), and he used it not to illuminate a vanished epoch but to produce a map of contemporary Japan that ranges from the complacent and affluent “heaven” to the needy and nihilistic “hell” of the film’s Japanese title, with an efficient police force patrolling the problematic zone where high and low collide. Kurosawa had treated modern themes before, to be sure. But High and Low is more detached in its effect: less heartrending than Ikiru, less savage (though no less contemptuous) in its criticism of corporate life than The Bad Sleep Well, less romantic in its attitude toward criminality than Drunken Angel. The tormented young policeman played by Toshiro Mifune in Stray Dog has grown up, perhaps, to be the coolly restrained detective embodied by Tatsuya Nakadai: seeing everything but keeping his judgments to himself until he really can’t take it anymore.

To underscore the film’s American provenance, Kurosawa gives us early on—in a close-up that intrudes with considerable shock effect into the deep widescreen vistas of the opening interior shots—the unleashed energy of a Japanese boy in a cowboy hat brandishing a toy six-shooter, the pure product of early sixties imported TV culture. Likewise, the central scene at police headquarters, in which the reports of each team are interspersed with visual clips of their investigations, conjures up the American documentary-style police procedurals of the postwar period, such as The Naked City and T-Men. The modern world in which High and Low takes place is unavoidably in some ways an American world—or perhaps the post-American world of a Japan still emerging from years of occupation and accustoming itself to a new era of unbridled economic development, bringing with it new kinds of social unease and dislocation.

The choice of material might seem curious. King’s Ransom, although like most of McBain’s books a good swift read, is not even one of the better novels in his “87th Precinct” series, lacking notably the raucous humor and offbeat characterizations that he usually brings to his police-station scenes. (McBain, born Salvatore Lombino, was also, as Evan Hunter, the author of The Blackboard Jungle and the screenplay for The Birds.) Kurosawa, in fact, kept little of the novel beyond its gripping premise—a businessman’s son is targeted by kidnappers, but they mistakenly abduct his chauffeur’s son instead—and claimed to have been impressed chiefly by the audacity of the kidnappers’ demand that the businessman nonetheless pay the ransom, a sum that will wipe him out. In King’s Ransom, the driven and arrogant shoe company executive Douglas King refuses to pay the ransom and lucks out anyway, saving both fortune and moral reputation; in High and Low, after initial resistance, Kurosawa’s protagonist, Kingo Gondo (incarnated by Mifune in a mode of fury just barely contained), accepts the moral imperative to save the boy and is, although not altogether destroyed, brought considerably down in the world.

From McBain’s tight little paperback thriller Kurosawa fashioned one of his most expansive and symphonic works, a film that immerses itself in the minutiae of the modern metropolis—pay phones, streetcars, garbage-disposal centers—while at the same time often approaching pure visual abstraction. The single shot in which undercover cops glance at a crooked mirror to watch their suspect ascending a staircase would not be out of place in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, yet in the context of High and Low’s visual design it is not even obtrusive. Kurosawa—whose first training was as an artist—once remarked that at least from Seven Samurai on, “[I] tried to add my sensitivity as a painter to what I hoped was my increasing know-how as a filmmaker.” The exceptional visual density of High and Low involves a double perception: every frame can be apprehended in terms both of the weightless, two-dimensional surface of a delicately composed painting and of the three-dimensional arena in which heavy bodies move and contend with reckless energy. (When Mifune’s Gondo notes, near the beginning, that “shoes carry all her body weight,” it only emphasizes the precise sense we always have in Kurosawa of the force displaced in each footfall.)

The director revels in the geometric play permitted by the widescreen ratio; we are positively invited to appreciate his constantly changing designs, as when Gondo opens curtains and a sliding glass door in abrupt horizontal movements analogous to the curiously old-fashioned wipes that were always Kurosawa’s signature form of narrative transition. The binding agent is the editing, with which Kurosawa, working often with footage captured from multiple angles simultaneously, freely cuts in and out of different spatial planes. There is no more conscious exercise in virtuosity in Kurosawa’s oeuvre. The bullet-train sequence, in which Gondo throws briefcases filled with ransom money through a bathroom window on the moving train while police detectives frantically film what ensues, runs less than six minutes and is rich enough in visual and rhythmic intricacies for a whole film.

These bravura technical flourishes are not a matter of gratuitous showing off. The controlled harnessing of energies that might otherwise spin out of control, the pulling together of the disparate material elements he’s working with, embody Kurosawa’s sense of morally purposeful action. The train sequence is immediately preceded by a scene in which the beleaguered Gondo, reminded of his origins as an ordinary shoemaker, takes out his old tool kit to assist the police in booby-trapping the briefcases with tracking devices, a gesture at once of humility and mastery. High and Low takes inventory of the capacities of the director’s own tool kit, with such concentrated intensity that every moment is in some sense climactic. We move in rapid cuts from one indelible visual formulation to another, each held barely long enough to take in before another replaces it.

The movements of Kurosawa’s symphony correspond to different locations: Gondo’s lavish apartment, with its commanding view of Yokohama, the narrow aisles of the bullet train, the sweltering police precinct, the lower depths where Gondo’s mansion becomes a reflection in garbage-filled water, and finally the prison where Gondo confronts his nemesis. Within these locations (each of which has its own distinct mood and narrative focus) there are openings to further spaces: the inner lining of a shoe, exposed to demonstrate its shoddiness; the picture of Mount Fuji over the sea, drawn by the kidnapped child (which will rhyme eventually with the actual Fuji, half visible through mist); the 8 mm movie of the retrieval of the ransom; the marks left on a writing pad by a drug addict’s frantic message; the illustrative fragments of urban geography interpolated in the precinct sequence; the murky hidden worlds of bars, drug-ridden alleyways, and cheap hotels; and the point of no return—the glass barrier in which criminal and victim each find the other’s face reflected.

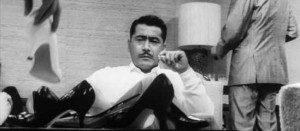

The definition of space is not only the method but the subject of High and Low. Everything pivots around the spatial relationship between Gondo, in his mansion on the hill, and the kidnapper, looking up from below in his airless shack. The first third of the film is confined chiefly to the limits of Gondo’s luxurious, modern, and, especially by Japanese standards, dazzlingly large living room. As the film begins, we are plunged into the final stages of a business meeting abruptly going sour, as the small-minded and rapacious executives of National Shoes fail to bring their colleague Gondo on board in their bid to cheapen the product line and take over the company. A mood of claustrophobia and hostility is established instantly as Gondo brandishes the cheap “new line” shoe sample like a sword and then proceeds to tear it apart with methodical rage. The scene at once invokes and parodies the string of samurai roles that Mifune had just played for Kurosawa.

Mifune’s whole performance is imbued with similar gestural allusions. Pacing back and forth in the throes of the business deal by which he plans to effect his own coup d’état at National Shoes, Gondo wields a drink and a telephone as if they were ritual objects bestowing occult power; and later in the film, when he asks the police to remain in the room during a business conference, it’s with the brusque, almost unconscious imperiousness of an overlord used to being obeyed. (In McBain’s novel, the police detest Douglas King and firmly put him in his place; in High and Low, Nakadai’s Inspector Tokura and his colleagues come to admire Gondo and serve his interests with devotion.) This subtext explodes into a stunning tableau when the chauffeur, Aoki, begging the reluctant Gondo to pay the ransom for his son, finally prostrates himself as if at the feet of a daimyo. As Aoki kneels at center screen, Gondo stands at the extreme right, looking downward and away, as if under unbearable pressure, while Inspector Tokura, seated at the other side of the screen and struggling to restrain his discomfort, looks leftward. The scene also occurs in King’s Ransom—“‘Do you want me to get down on my knees, Mr. King? Shall I get on my knees and beg you?’ He dropped to his knees, and [detective] Carella winced and turned away”—but with nothing like the layers of historical resonance and emotional complication that Kurosawa is able to suggest in a single serene composition.

From samurai to shoe manufacturer: Gondo retains the combative instincts and self-conscious pride of an earlier era while struggling to reconcile himself to life as a company man. Much like Kurosawa (who had left Toho to form his own production company in 1960) fending off the perceived cheapening of Japanese cinema, Gondo touts the virtues of his own individualistic path: “I’ll make my ideal shoes: comfortable, durable, yet stylish. Expensive to make maybe, but profitable in the long run.” With his apparently traditional and compliant wife, Reiko (Kyoko Kagawa), at his side, Gondo seems poised to oversee a paean to craft-minded entrepreneurship along the lines of Robert Wise’s Executive Suite. But with the kidnapper’s phone call we are quickly knocked out of that movie—the first of many sudden shifts of focal point. In most films involving a kidnapped child, for example, the fate of the child remains in play until the last reel; here we know his fate a third of the way through, and can survey the police hunt for the kidnapper without that emotional distraction.

High and Low in a sense is a film with no center, or a film whose center is everywhere: it is concerned with mapping all the human contacts, no matter how tiny or apparently insignificant, that fall within its scope. Gondo may be the samurai hero of his own drama, but in the course of the film he will be seen from many angles, and often—for most of the second half—he will disappear from view altogether. He has his grand plan to seize control of National Shoes, just as the kidnapper has his grand plan to commit a perfect crime and exact an immense ransom. The film’s own grand plan is to keep turning the plot around to look at it from other angles, through different eyes.

The real hero might be neither Gondo nor Inspector Tokura but the bald, blunt, bull-like Head Detective Taguchi, a working-class hero of the oldest school who can barely hold back his contempt for the weaselly executives of National Shoes when they hang Gondo out to dry; or perhaps Aoki, who suffers not only the loss of his child but the intolerable burden of having him restored at his employer’s expense, placing him in the position of having received a gift he can never repay and that has destroyed the giver; or, most appropriately, the kidnapped child, Shinichi, who keeps cool enough to record precise impressions of his surroundings and of his kidnapper and who interrupts the unobservant adults to call their attention to the film’s most unexpected visual effect: the pink smoke signaling that the kidnapper is burning the booby-trapped briefcases in which he collected the ransom.

We might even want to bring to the center for a moment the discreet, sometimes almost invisible presence of Gondo’s wife; it is she, after all, who tells him from the outset that “success isn’t worth losing your humanity,” and whose understated moral suasion directs his ultimate course of action. (Aside from two heroin addicts who both turn up dead, she is the only significant female character in the drama—not surprising, perhaps, from a director who once told Donald Richie that “women simply aren’t my specialty.”)

The pink smoke—the only burst of color in a black-and-white film—marks the moment when the film definitively descends from heaven to hell, the point of entry being a dump that burns “everything that can’t be disinfected.” This is the juncture when those above finally take notice of the life below them, even if only in the form of burned evidence. Those below, on the other hand, could always see what was above them. “From down there,” as the inspector notes on his arrival in Gondo’s apartment, “if he’s got a telescope, the kidnapper can see this entire room.” The kidnapper, then, has possessed from the beginning the same power as Kurosawa’s camera: to command space and find every hiding place within Gondo’s seemingly impregnable aerie. To hide from those eyes, even the police are forced to crawl on the floor.

The kidnapper, a medical intern named Ginjiro Takeuchi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), wears dark glasses, the badge of the lurker who sees without being seen. He does not speak on-screen until the last scene of the movie—even then refusing to divulge his story or his real motives. The police-hunt for Takeuchi tells us little about him but much about Kurosawa’s vision of the nether regions of modern Japan. The luridness of that vision—a swirl of noisy bars with multiracial clienteles and dark side streets swarming with drug addicts who resemble the incarcerated lepers of Fritz Lang’s fantasia The Indian Tomb—is now, as it was on first release, the least persuasive aspect of High and Low. The imagined horrors of that murky inferno simply cannot compete with the clearly delineated nastiness of the National Shoes executive team, for all the expressive beauties of the camera work that Kurosawa brings to bear.

But the structural force of his conception holds firm right through to that devastating (and much-analyzed) confrontation between Gondo and Takeuchi as the latter awaits execution. Nothing is more powerful about this scene than its refusal to provide any disclosure that would explain what we have just been through. What the kidnapper offers finally is not an explanation but a scream of pain. As the guards whisk him out of sight and a dark barrier descends in front of Gondo, the effect is like the typical brusque ending of a Noh play, as ghost or demon vanishes and the chorus intones: “And thereupon the spirit faded and was gone.”

In place of some clarification of what all this might mean, then, we are left with Gondo alone, facing a blank barrier. At the beginning of the movie, caught up in the effort to grab the company’s power for himself, he was already treading a dangerously individualistic path. Now he has finally succeeded in being fully alone in a society in which lives impinge relentlessly one on another, and has thereby—whether he wanted to or not—achieved the solitariness that was the kidnapper’s whole identity. The two have essentially become one—but we already knew that from the way the face of each, staring through the glass, was superimposed on the other. Takeuchi is a demon of isolation, defiantly cut loose from those indispensable ties of human contact that are measured throughout every frame of High and Low by a constant play of glances and postures. Hierarchies and group identities, and the impulses that can undermine them from within, are charted so clearly that we can draw the invisible lines connecting any character with any other character. From moment to moment they cannot help but show us where they are. The space to which Kurosawa devotes such consummate skill is a space defined by human relations, and is thus necessarily a space of constant turmoil, pressure, and struggle, right up to the moment when the barrier slams shut.

-Geoffrey O’Brien

Are there cultural purists still remaining who would argue that the “Westernized” title of Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 masterpiece—High and Low—throws polluted water on the cosmological fire of its given name: Tengoku to jigoku—literally, Heaven and Hell?

Kurosawa’s once insisted-upon reputation as Japan’s most “Western” filmmaker aside, the director whose go-for-baroque Rashomon decisivelyopened international eyes to Japanese filmmaking was rarely shy about his American tar-pit pleasures—even if he demurred from acknowledgingYojimbo’s suspicious indebtedness to Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. Highand Low, as its credits admit, was adapted from a long-forgotten pulp policier titled King’s Ransom, one in a series of “87th Precinct” novels written by Evan Hunter under the nom de potboiler-maker “Ed McBain.”

Building on the whirlingly Wellesian The Bad Sleep Well—Kurosawa’sprevious modern-dress meditation on narrative fragmentation and moral decay—High and Low makes good on its title by grooving on twitchy, tawdryrock n’ roll, painstakingly ladling sewage on Schubert’s “Trout” quintet, and intensifying the climax of its murder investigation with a rinky-tink radio broadcast of “It’s Now or Never.” Purists still unimpressed by these cultural interpolations might at least be thankful that the film wasn’t titled The Devil Wears Mirrored Shades.

That is, after all, what the film’s villain, Takeuchi (an aspiring Satan trapped in the scarred body and tormented soul of an impoverished medical student), sports during the film’s climactic episode. Or rather, during one of its many climaxes, as High and Low is a thriller flush with needle-spiking tensions and bullet-train exhilarations.

An anti-Narcissus adrift in a narcotic-saturated, discotheque-driven nightworld, the mirror-shaded Takeuchi (played by Tsutomu Yamazaki, whomatured into the Gregory Peck-ish star of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo) has developed a diabolical obsession. He longs to reflect the charred chaos ofmodern Japan’s lower depths back into the face of the most successful manhe can find. As he gazes out the window of his stifling, three-tatami Hell—deep somewhere in Yokohama’s summer cauldron—Takeuchi has little difficulty in locating a celestial fortress from which to bring a flourishing sky king low.

His target-on-high: a self-made footwear magnate crowned Kingo Gondo, theindestructible shank in the sole of the National Shoes company.

As furrowed forth by a ferociously contained Toshiro Mifune, Gondo may live in the proverbial house on the hill—an impeccably emptied-out mansion that seems to look imperiously down on the entire city below—but he remains a man rooted in a humble, hands-on past. “Shoes carry the weight of the whole body,” Gondo huffs early on, denouncing the shoddy pumps hisprofits-over-quality corporate partners intend to bring to market. A well heeled exec with one foot in the past (he still keeps his shoe-repair tools within easy reach), Gondo thinks he’s already one step ahead: He’s made plans to outmaneuver the company takeover his partners are about to attempt.

What Gondo can’t foresee is Takeuchi’s plan to stamp on his toes with aplot to kidnap Gondo’s son and demand a ruinous, king(o)’s ransom. Theplan goes through, but when the gambit hits a minor snag—Takeuchi’s henchmen nab Gondo’s chauffeur’s son by mistake—he demands the ransom anyway, setting in motion a moral dilemma worthy of Kingo Solomon. Should Gondo pay the ransom and save a child not his, at the expense of losing his company and heavily-mortgaged home? Or sacrifice the child and save his position, high on that hill, while his hardened soul plummets into the mirror-world below?

The existing literature is rich with praise for High and Low’s screw-tightening first hour, as Gondo, a group of zealous cops, and Kurosawa’s anamorphic lens remain locked in the mansion’s living room, fielding the kidnapper’s phoned-in demands. It’s an astonishing episode, built on elaborate permutations of group- and individual-formation, mixing two-shots and seven-shots into icy cameos and exponentially enervated group portraits. But once it shifts into its investigatory second hour, the film’s true flowers unfold. Textures of groups of men in motion alternate with hyper-detailed sequences of evidence-analysis that suggest the scrutiny of Abraham Zapruder’s contemporaneous 8mm footage from Dallas. And Chez Gondo, once seen from Takeuchi’s vantage, begins to assume Psycho proportions. Clues mount, attitudes and directions change, and finally an astonishing plume of crimson-pink smoke signals an opening into the pit—welcoming the viewer as Kurosawa’s camera plunges in.

Behold, at last, the Low: a sordid sin-market filled with mixed-race couples and manic frugging, squabbling sailors and cat-eyed slatterns, ravaged junk-zombies and undercover cops from Hell. Here, talk is useless and chaos holds supreme, and in all of Kurosawa’s filmmaking, there is nothing else quite so chaotic and obscene.

What could have ignited this blackened gust? Was this, perhaps, the soon-to-fade master’s furious reply to the go-go nihilism of the then-rising Japanese nouvelle vague? A bitter, full-blast bettering of the Noh-exit excesses of early Oshima’s Japan-as-buried-sun and the still-to-come cartoon cruelty of the “incomprehensible” Seijun Suzuki? And is Takeuchi’s admission, shortly before High and Low’s metallic closing curtain bangs shut—”I’m not interested in self-analysis”—Kurosawa’s last word on his long-held passion, the heroism of the individual?

The answers are here, if forged in a climax—as befits the film’s precipitous reversals of fortune and exalted failures—hidden in plain sight somewhere well before The End. High on a hill overlooking modernity’s inferno, Kingo Gondo wears the imperial robe of the economic miracle: a well-starched dress shirt and beneath, a clinging tee. And on that robe Kurosawa paints in stinging brushstrokes an image as stubbornly resigned to toil as any in modern cinema. The lapsed millionaire, his body covered in salty Rorschach blots, pushes his own lawnmower, determined to slay the weeds that claw ever upward from below. Weeds that threaten to choke the well-manicured lawns and far-from-Zen turf-gardens of postwar Japan’s altogether earthly domain.

-Chuck Stevens

What makes Akira Kurosawa’s film High and Low much more than a standard thriller is it’s other powerful themes that Kurosawa incorporated into the story. What Akira Kurosawa did with the original material was shape it to produce a film that was a reflection and a contemporary map of Japan that ranges from the complacent and the rich, to the needy world of drugs despair and the poor. The film’s themes are more similar to corporate life of The Bad Sleep Well and the early noirs of Stray Dog. The early shots of the film before the kidnapping show his son Jun and Shinichi in a cowboy get-up, which was an homage to Kurosawa’s love for American Westerns and for the great American director John Ford.

Whats interesting about the layout of this film is that there’s no real center, just two different halves. The first half tells the story of Gonzo’s life changing dilemma of him willing to lose everything, all for a child that is not even his. The first half to me is the heart of the picture because Toshiro Mifune portrays a ruthless and cold businessman who’s willing to step on others to get to the top. The second half of the film is more of a police procedural which focuses on Tokura and his men following clues, conducting interviews and investigating old audio tapes and photographs. Eventually they do find the kidnapper but at this point it’s already two late since Gondo has already been forced out of the company and his creditors demand the collateral in lieu of debt; which make him completely broke. I have always believed that in a film it’s more interesting to reveal the villain to the audience early on and have the audience try to understand how they work and how they think. Most films make the villain or monster (especially in horror films) identity a mystery until the very end, but I believe that’s a cheap cop-out for a really good story. Some of the best films show the identity of the villain earlier on like in Fritz Lang’s M or George Sluizer’s The Vanishing, and it’s more interesting to learn why the villain is doing these horrible acts then to make them some one-dimensional faceless killer that has no real character development whatsoever. It was much more intense to watch this medical intern try to allude the police, and to see how far he could go to outsmart them and try to get away with the money he stole. That’s why films like The Silence of the Lambs, and Se7en are more interesting than most thrillers because you get inside the head of the villain instead of making them this shadow hiding in the dark with a butcher knife. High and Low is a suspenseful classic that portrays the poor drug induced areas of Japan and the rich high scale areas as well. It shows the different classes between the rich and poor and sometimes what jealousy and hate can lead someone into doing. It also shows the rivalry of large corporations and business owners and how greed can lead to sacrificing others to move yourself up for greater money and power. In some ways the both of them are very similar, because they both are power-hungry individuals who don’t like to show fear or mercy. The both of them also had their own diabolical get rich schemes in which one worked within the law and the other one worked outside the law; and yet in the end they both failed. I pity Takeuchi because I can somewhat understand why this medical intern who is struggling to move up in the corporate world started feeling hatred and jealousy for the wealthy. You feel his contempt for Gondo as he leaves his crummy studio apartment to head to a grunt job everyday and having to always see Gondo’s palace high up on the hills. Many of Kurosawa’s best films focused on the themes of social classes and the rich and the poor including The Seven Samurai, Dersu Uzala, Red Beard and Ikiru. When Takeuchi reveals to Gondo why he did what he did, his explanation is so simple and understandable that anyone who lived poor could understand his motives. “My room was so cold in winter and so hot in summer. I couldn’t sleep. From my tiny room, your house looked like heaven. Day by day I came to hate you more. It gave me a reason for living. Besides, it’s amusing to make fortunate men taste the same misery as the unfortunate. You want my life story? Forget it. I won’t share my tales of woe to earn your sympathy. I’m glad my mom died last year so I won’t be sickened by her pathetic slobbering. I’m not afraid of death. I don’t care if I go to hell. My life has been hell since the day I was born! “

Whats interesting about the layout of this film is that there’s no real center, just two different halves. The first half tells the story of Gonzo’s life changing dilemma of him willing to lose everything, all for a child that is not even his. The first half to me is the heart of the picture because Toshiro Mifune portrays a ruthless and cold businessman who’s willing to step on others to get to the top. The second half of the film is more of a police procedural which focuses on Tokura and his men following clues, conducting interviews and investigating old audio tapes and photographs. Eventually they do find the kidnapper but at this point it’s already two late since Gondo has already been forced out of the company and his creditors demand the collateral in lieu of debt; which make him completely broke. I have always believed that in a film it’s more interesting to reveal the villain to the audience early on and have the audience try to understand how they work and how they think. Most films make the villain or monster (especially in horror films) identity a mystery until the very end, but I believe that’s a cheap cop-out for a really good story. Some of the best films show the identity of the villain earlier on like in Fritz Lang’s M or George Sluizer’s The Vanishing, and it’s more interesting to learn why the villain is doing these horrible acts then to make them some one-dimensional faceless killer that has no real character development whatsoever. It was much more intense to watch this medical intern try to allude the police, and to see how far he could go to outsmart them and try to get away with the money he stole. That’s why films like The Silence of the Lambs, and Se7en are more interesting than most thrillers because you get inside the head of the villain instead of making them this shadow hiding in the dark with a butcher knife. High and Low is a suspenseful classic that portrays the poor drug induced areas of Japan and the rich high scale areas as well. It shows the different classes between the rich and poor and sometimes what jealousy and hate can lead someone into doing. It also shows the rivalry of large corporations and business owners and how greed can lead to sacrificing others to move yourself up for greater money and power. In some ways the both of them are very similar, because they both are power-hungry individuals who don’t like to show fear or mercy. The both of them also had their own diabolical get rich schemes in which one worked within the law and the other one worked outside the law; and yet in the end they both failed. I pity Takeuchi because I can somewhat understand why this medical intern who is struggling to move up in the corporate world started feeling hatred and jealousy for the wealthy. You feel his contempt for Gondo as he leaves his crummy studio apartment to head to a grunt job everyday and having to always see Gondo’s palace high up on the hills. Many of Kurosawa’s best films focused on the themes of social classes and the rich and the poor including The Seven Samurai, Dersu Uzala, Red Beard and Ikiru. When Takeuchi reveals to Gondo why he did what he did, his explanation is so simple and understandable that anyone who lived poor could understand his motives. “My room was so cold in winter and so hot in summer. I couldn’t sleep. From my tiny room, your house looked like heaven. Day by day I came to hate you more. It gave me a reason for living. Besides, it’s amusing to make fortunate men taste the same misery as the unfortunate. You want my life story? Forget it. I won’t share my tales of woe to earn your sympathy. I’m glad my mom died last year so I won’t be sickened by her pathetic slobbering. I’m not afraid of death. I don’t care if I go to hell. My life has been hell since the day I was born! “